A big Bantu table

Jenneke van der Wal reflects on her research project BaSIS, which aims to systematically investigate the influence of information structure on syntax in a subset of Bantu languages.

It all started during my first postdoc project when I found myself daydreaming about a table. You know, one of those tables you can insert in a Word doc, or make with Excel. But my particular table was one that included many, many rows and columns; ideally a row for each Bantu language. And since there are about 555 languages in the Bantu language family, spoken between Cameroon, Kenya, and South Africa, it would be a long, long table. My daydream table would also have many columns; at least enough columns to include all the aspects of information structure that I wanted to discover in these languages. Information structure is the way speakers package the information in a sentence to fit with the attention of the addressee: what is old, what is new, what is contrasted with earlier information? And so, as there are many aspects to information structure, the table would need to be very wide as well.

Bantu languages and information structure

Before I elaborate on my big Bantu table, let me first tell you a bit about information structure and why it is particularly interesting to study when it comes to Bantu languages.

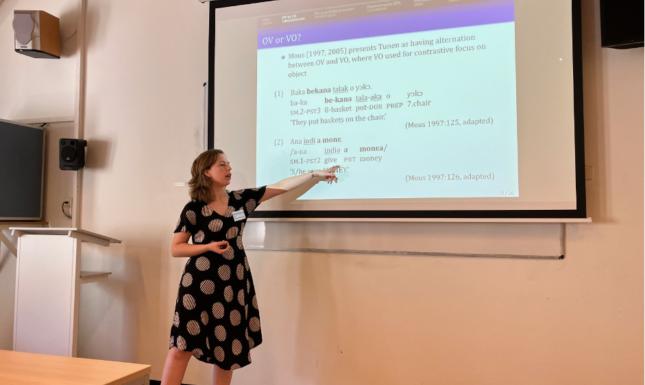

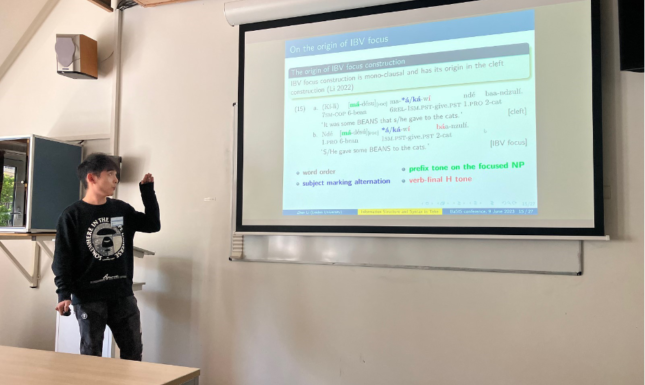

In English, intonation can be used to express a contrast, for example ‘We ate PANCAKES’ to suggest that we didn’t eat broccoli, like the addressee might have thought. The Bantu languages typically do not use intonation, but rather build the information structure into their grammar. For example, in Rukiga (spoken in Uganda), if a word refers to old information in the conversation, because we have already mentioned it, it will be in an initial position, like the ‘birds’ in (1). But if the birds form the new information that the listener needs to focus on, as in (2) (when we don’t know about the birds yet), then it must follow the verb. In other words, the word order is influenced by what is old or new information.

- (What about the birds, where do they sleep?)

Enyonyi ni-zi-raara omu muti.

birds IPFV-they-sleep in tree

‘The birds are sleeping in the tree.’

- (What about the tree, who sleeps there?)

Omu muti ni-ha-ráara=mw’ ényonyi.

in tree IPFV-there-sleep=there birds

‘In the tree sleep the birds.’

The above examples point to the importance of information structure in describing and understanding the grammar of Bantu languages, more so than grammatical functions such as ‘subject’ or ‘object’. I realised that ‘subject’ or ‘object’ grammatical functions might work well for European languages, but Bantu languages seemed to have a fundamentally different basis, and therefore require a different theoretical perspective too. The idea for a research project was born (and subsequently funded by the Dutch Research Organisation NWO). I called it ‘Bantu Syntax and Information Structure’ (BaSIS).

Setting up the BaSIS team

But my daydream table was still a long way off from becoming a reality; how was I going to even start filling the table when I wasn’t able to speak any of the languages properly?

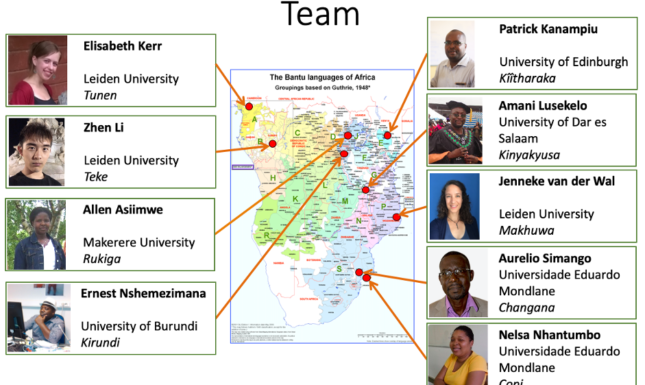

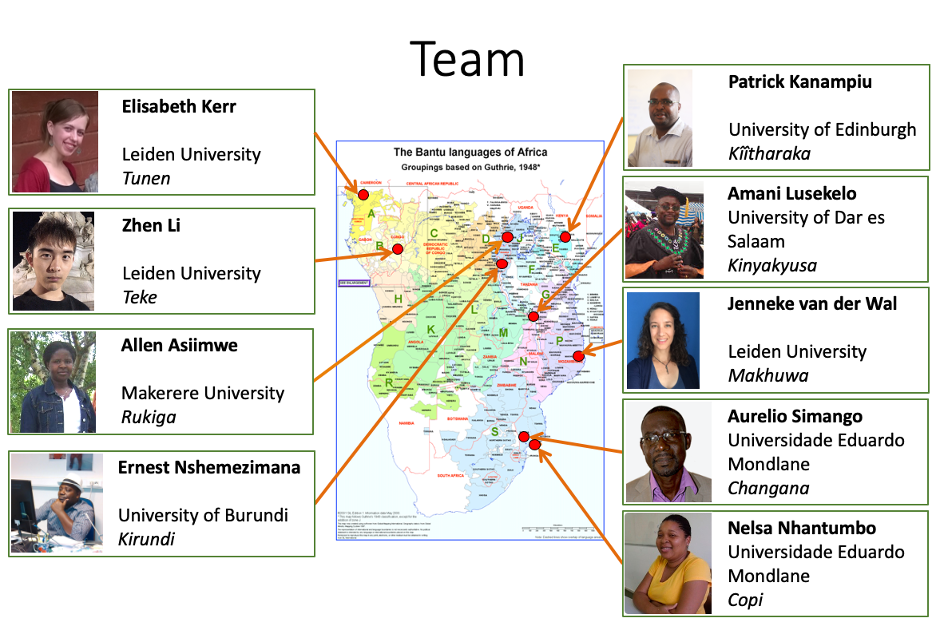

This is where collaborative linguistics comes in: besides two PhD students (Elisabeth Kerr and Zhen Li), our team included seven native speaker linguists at African universities (Allen Asiimwe in Uganda, Aurélio Simango and Nelsa Nhantumbo in Mozambique, Patrick Kanampiu in Kenya, Amani Lusekelo in Tanzania, Ernest Nshemezimana in Burundi, and Jekura Kavari in Namibia). The collaborations had their challenges, of course, with intercultural differences in expectations and the loss of two collaborators from the project. Nevertheless, using both inside and outside perspectives helped us better understand the languages we were studying.

And then there was COVID

At the start of 2020, we had a team, we had a (constantly developing) methodology, and we had collected our first data on six of the languages. The cells of the Bantu table were slowly being filled. All was looking bright, until Covid-19 hit, and fieldwork was no longer possible. Just like everybody else, we had to adjust. Our weekly tea meetings moved online, we continued analysing the data we had already collected, and we created video presentations for virtual conferences. But at some point, the data dries up, and the end of the project was coming eerily close. An extra challenge was that even after restrictions were lifted, the university remained very hesitant to allow researchers to conduct fieldwork. A lot of effort was spent to make fieldwork possible again (including an opinion piece in the Leiden university newspaper Mare). When we were finally given the go-ahead and collected further data, we were able to begin with the comparative aspect of the project, asking questions such as:

- How is word order used in the expression of information structure in each of the languages?

- If we find the same strategy in several languages, does it have the same interpretations and use?

- Which strategies do our languages use to stress that something is really true?

Partial answers to these questions were discussed during the final BaSIS conference, held on 8-9 June 2023. They will also be forthcoming in publications, so keep an eye on the BaSIS project website.

One step closer to realising my big Bantu table

As of today, 18 July 2023, the project is officially over. Our book describing the expression of information structure in those Bantu languages we collaboratively and systematically studied during BaSIS, is almost finalised. This means that I am exactly 1,62% closer to filling in my big Bantu table (with 9 out of 555 languages)… While this is only a tiny percentage, it is a very important percentage, because it sets an example of how investigating information structure in Bantu is crucial and it is possible. This will hopefully inspire others to contribute to our understanding of Bantu syntax and information structure. It is exciting that Simon Msovela, who was a research assistant in the Tanzania subproject, has already started investigating information structure in Kihehe for his PhD! Jointly we can achieve more than alone, and until the day the big Bantu table is filled, I will keep daydreaming and investigating.

Project details

For all information, including a detailed project description, our researchers, an overview of our past activities, our methodology, and our resulting publications, please visit the BaSIS website.

BaSIS website